Brain’s Optimal Amount of Sleep every Night

Written by: Alexandra Kifak, BSc.

Reviewed and edited by: Gargi Deore, BSc, MSc.

Focus Paper: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11910-023-01309-8

Is Being Asleep for a Third of Our Lives Worth It?

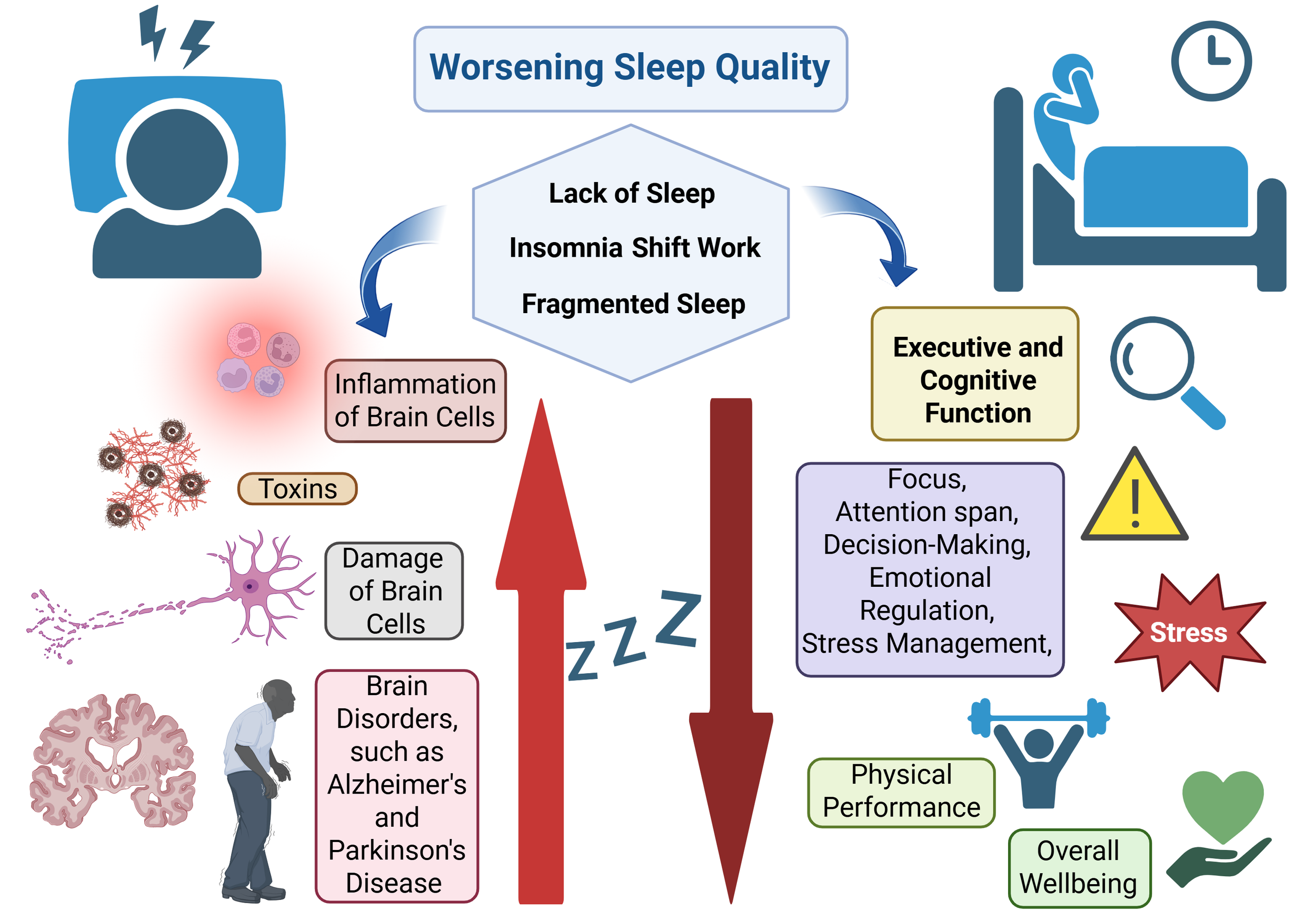

As humans, we spend about 33% of our life asleep. Assuming an 80-year lifespan and 7-8 hours of shut-eye each night, that amounts to about 26 years spent sleeping. Where does this time go? Is it just wasted? It is a fair question to ask. Lying down passively instead of doing, achieving, or pursuing our dreams and goals can feel unproductive. And while “you’ll sleep when you’re dead” hustle culture glorifies sacrificing sleep, sleep deprivation can lead to a bounty of damaging effects, especially for the brain and nervous system. In our central nervous system (CNS), lack of sleep can manifest as trouble focusing, poor decision-making, worsened memory, impaired critical and creative thinking, as well as stress, anxiety and mood swings. Essentially, both cognitive and executive functions - necessary to process information and execute tasks - effectively are severely impaired. Moreover, recent compelling research shows that people who sleep less than 6 hours per night in their 50s, 60s and 70s have a 30% higher risk of developing dementias such as Alzheimer’s disease (1).

In this article, we will explore the essential importance of the right amount and quality of sleep each night by dissecting the recent scientific review titled “Sleep Duration and Executive Function in Adults” published by neuroscientists Aayushi Sen and Xin You Tai in 2023 in Current Neurology and Neuroscience Reports, a peer-reviewed journal from Springer (2). This study synthesizes findings from multiple peer-reviewed articles to identify commonalities and gaps in research and summarize existing opinions on sleep in the field of sleep neuroscience.

Why Getting Enough Sleep Isn't Just Rest—It's Brain Work

What is sleep, anyway? Sleep is a complex physiological process, which is evolutionary essential for restoring brain and body function. While it may seem that nothing much is happening during these nightly shut-eye hours, the truth is that your brain is in an active state of recalibration and reboot. The brain switches from non-rapid eye movement (NREM) and rapid eye movement (REM) stages roughly every 90-minutes (about 80% NREM, 20% REM). NREM deep sleep is more common at the beginning of the night with REM stage becoming progressively longer closer to the morning hours. This is easily explained by the function of each stage. NREM sleep preserves memories accumulated from the day by moving them from short-term to long-term storage and clears out mental “trash”, such as toxins. REM sleep is where the dreams occur, your eyes move rapidly, muscles are limp and valuable memories are strengthened as new creative connections from between neurons.

Executive Brain Function: What is it and How to Measure It?

Executive function of the brain refers to a set of cognitive processes, including attention, planning, problem-solving, self-control, memory, and the ability to juggle multiple tasks at once– all essential to carry out goal-driven actions, such as cooking, acting or performing a surgery. It naturally declines with age, but is especially impaired in neurological conditions, such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Disease. Research papers reviewed in the focus study measured the executive function using neuropsychological task tests such as the Trail-Making Test, Stroop Test and Digit-Symbol Substitution Test. All these tests reveal cognitive flexibility, speed of response and ability to sustain attention and focus on the tasks at hand. Information was collected both through questionnaires and lab tests.

Biological Processes Behind Low Executive Function on Low Sleep

Sleep isn’t optional for a healthy brain. Numerous studies show that lack of sleep disturbs executive function – our ability to plan, focus, regulate emotions, and perform tasks. Furthermore, chronic sleep deprivation is linked to detrimental pathological processes within the brain. Firstly, lack of sleep raises inflammation within the brain (neuroinflammation), which disrupts normal function of neurons and other brain cells. Secondly, glymphatic drainage system in the brain responsible for clearing out toxins such as amyloid-beta (associated with Alzheimer’s disease) fails to do so sufficiently. Lastly, neuroinflammation and accumulated toxins can lead to neurodegeneration, which involves the destruction of previously healthy neurons, a major risk factor for diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease. Some studies show that even the volume of the brain can change due to insufficient sleep!

Image 1: Biochemical Damage of Low Quantity and Low Quality Sleep. Generated via BioRender by Alexandra K.

Optimal Sleep: Not too Short, Not too Long

After examining numerous research papers on the optimal duration of sleep for adults, focus review by Aayushi Sen and Xin You Tai revealed around 7-8 hours per night to be a “Goldilocks zone” for sleep length for an adult (18-65 years old). Participants who slept less than six hours per night showed the poorest executive function, with weak attention span, heightened irritability, and impaired decision-making. However, most surprising finding was that sleeping too much is also not good for you! One UK Biobank study of nearly 480,000 adults (ages 38–73) found that executive function and cognitive performance declined for every hour of sleep below or above this ‘sweet spot’, a trend that held true even in adults over 60 (3). In other words, sleeping less than 6 hours or more than 9 hours persistently, not just once-off, is bad for your brain’s executive function and ultimately, for your brain health. Furthermore, with every hour of sleep away from the 7–8-hour baseline, the damage to cognitive function worsens. Regarding long sleepers, it’s important to note that a person inclined to sleep for more than 11 hours every night can be affected by other conditions such as depression or anxiety, which were not always included and accounted for in the study measurements. Meaning that the length of sleep is not the primary cause of distress in such a person’s life, but a following consequence of underlying emotional or psychological struggle, which often worsens executive function independently of sleep length (4).

For Sleep: Quality and Quantity Both Matter, Not Just One or the Other

Most fundamental message of the chosen review and emerging discoveries is that the quality of sleep matters as much, if not more, than the quantity. So far in sleep research, sleep duration has been used as the main measurement to correlate with cognitive performance and executive function, or other health effects measured. But studies now point out that sleep efficiency might be the key influence on brain health. Hormonal shifts, stress, artificial light pollution in cities, diet and sleep disorders are all factors that can affect our sleep quality. Poor quality sleep or sleep that is frequently interrupted can interfere with the glymphatic system trying to clear out all the toxins from the brain at night. If proper brain clearing does not occur, accumulation of waste products, such as used proteins and other metabolic byproducts, can disrupt neuron function and lead to neurodegeneration. This in turn may lead to development of brain diseases, such as dementia.

Silent Sleep Loss Epidemic

Inadequate sleep is an issue that runs deeper than a teenager scolded for staying up late. The implication is beyond the shut-eye when body rests. It’s the exhausted surgeon on their 24-hour work shift who made a mistake and lost patient’s life due to unethical working hours established by the medical system. It’s the selfless pilots who claim to be night owls but must keep telling each other jokes to stay awake during flights. And it’s the disturbing statistic that drowsy driving is equivalent to driving drunk. Research shows that deficits in motor performance due to sleep deprivation are equivalent to a blood alcohol content of 0.05–0.1%, which is comparable to the legal driving limit of 0.08% in England and the USA (5). Another striking study revealed that a drowsy driver is 29% to 34% more likely to get into a car crash (6).

Unfortunately, effects of sleep deprivation reach far and wide in our society ranging from impulsive decisions by politicians and business makers to heavy bags under the eyes of single mothers. Partially, that is due to lack of awareness on just how crucial sleep is for our brain health and ability to be a regulated and helpful individual in society. This is the reason why I am writing this article, and why many neuroscientists are involved in education initiatives globally. All to support what sleep scientist and author of Why we sleep, Matthew Walker calls a “silent sleep loss epidemic.” Your takeaway from this read is that your brain needs 7 – 8 hours of quality sleep per night, consistently, for its ultimate healthy function. My genuine hope is that if you are reading this Neuro-bite article in the evening, you are fast asleep by now.

Sweet dreams.

References:

1. Sabia S, Fayosse A, Dumurgier J, van Hees VT, Paquet C, Sommerlad A, et al. Association of sleep duration in middle and old age with incidence of dementia. Nature Communications. 2021;12(1):2289.

2. Sen A, Tai XY. Sleep Duration and Executive Function in Adults. Current Neurology and Neuroscience Reports. 2023;23(11):801-13.

3. Tai XY, Chen C, Manohar S, Husain M. Impact of sleep duration on executive function and brain structure. Communications Biology. 2022;5(1):201.

4. van Oostrom SH, Nooyens ACJ, van Boxtel MPJ, Verschuren WMM. Long sleep duration is associated with lower cognitive function among middle-age adults – the Doetinchem Cohort Study. Sleep Medicine. 2018;41:78-85.

5. Williamson AM, Feyer AM. Moderate sleep deprivation produces impairments in cognitive and motor performance equivalent to legally prescribed levels of alcohol intoxication. Occup Environ Med. 2000;57(10):649-55.

6. Moradi A, Nazari SSH, Rahmani K. Sleepiness and the risk of road traffic accidents: A systematic review and meta-analysis of previous studies. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour. 2019;65:620-9.